Wastage is a huge pain point for fruit production, export, and retail—it is a primary financial drain as well as an ethical and environmental crisis. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) states that 13.2% of all food produced is wasted after harvest before it even reaches the retailer [ref], with staggering losses in fruit specifically reaching up to 50%.

However, the tide is turning. The integration of advanced quality control technologies is now the primary lever for reducing waste and recovering lost margins. By moving away from subjective checks, producers can eliminate the hidden defects that lead to rejected shipments and costly claims.

Navigating the Technology Landscape

We now live in a world of proliferating technology, with everything from Near-Infrared (NIR) to Hyperspectral Imaging (HSI) and clinical-grade X-ray claiming to solve the industry’s transparency problems. For businesses under pressure to cut waste and meet ever-higher consumer standards, getting lost in the marketing jargon is easy - but making the right choice is critical for long-term survival.

This article provides a comparative deep dive into the leading technologies in fruit quality control. We will explore how different innovations stack up against the critical challenges of the modern packing line:

- Eliminating the Cost of Claims: Detecting internal rot and blemish-free exteriors that hide "invisible" defects.

- Replacing Guesswork with Data: Moving from manual sampling to 100% non-destructive inspection of every piece of fruit.

- Building a Competitive Edge: Using precision grading to distinguish your brand in a crowded global market.

While no single tool is a silver bullet, the shift toward a zero-waste supply chain depends on matching the right technology to your specific operational pain points. Let’s look at how the current industry standards compare to the next generation of internal imaging.

Visible Light

Visible light photography is a technology we now all hold in the palm of our hand. It has the ability to provide stunning, high-resolution images of an object's surface in fractions of a second - yet it is powerless to look below the surface of an apple, or an avocado.

Most fruit are partially or entirely opaque to visible light, meaning that upon incidence to the fruit surface, the light is primarily scattered and absorbed rather than transmitted further, obscuring information from farther within. The reason for this is simply that the wavelengths of light that we can see with our own eyes are preferentially absorbed and scattered by fruit.

But what about all the light we cannot see?

The Early Pioneer - NIR Sensing

Astronomer William Herschel discovered infrared (IR) radiation in the year 1800, the first inference of light beyond that which we can see with our eyes [ref]. Now, over 200 years later, near-infrared (NIR) spectroscopy methods are the industry standard for looking below the outer surface of fruit, with the first use in fruit quality control recorded as early as the 1950s [ref, ref].

So, what changed? NIR light has a longer wavelength than visible light, and therefore interacts very differently with structures in (fruit) tissue.

It can penetrate farther into many materials, and by measuring the light that is reflected, transmitted, or absorbed by the sample, one can make predictions on what is “going-on” below the surface. At the same time, it is non-ionising and safer to use than high frequency radiation such as X-rays.

More specifically, the data recorded contains what is known as the “spectral fingerprint” of the sample, from which we can learn what chemical components inside the fruit have absorbed light at known wavelengths. This in turn gives information as to chemical and structural changes inside the fruit, such as bruising, rotting and ripening.

NIR-based sensing is highly versatile, and the exact technique today can vary by application. Devices come as handheld, portable units for use in the fields, or can be integrated in-line in the packing houses as part of larger automation systems.

The exact wavelength of IR radiation used is optimized for the sample and feature of interest, and penetration depths of up to 5 mm are typical for an avocado - a huge advancement from visible light.

Yet fruit with thicker skin, such as watermelons, are technically “invisible” to NIR sensing; the light physically cannot reach the edible parts of the fruit, much like our phone cameras. The limit on penetration depth is a physical consequence of the scattering properties of NIR light in tissue, and is not something modern technology can easily surpass.

While NIR’s legacy in fruit quality control is undeniable, its performance is curbed by its inherent limitation of penetration depth. It remains an effective sensor for quality control of external surfaces, and for sugar or dry matter measurements from shallow regions below the surface, but it is relatively insensitive to the deep tissue effects of rotting and browning for example - precisely what inflates losses in fresh produce.

*Performance depends heavily on what is measured and the sample that is measured from.

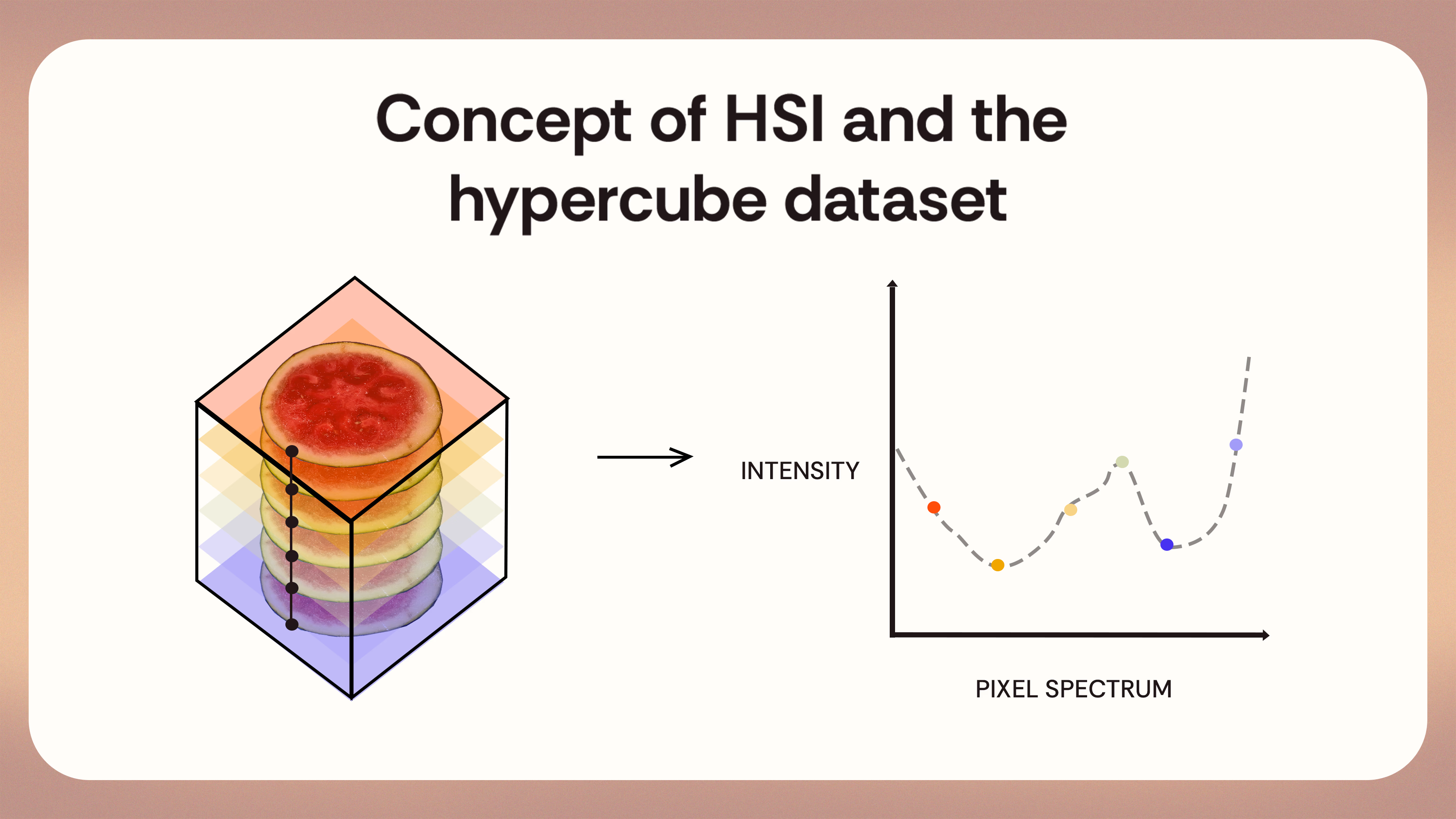

Hyper-Spectral Imaging

A relatively new technology to arrive on the scene is Hyper-Spectral Imaging (HSI), originally developed in the 1980s by NASA as a remote sensing method to measure vegetation health, locate mineral deposits, and map the Earth's surface from orbit [ref]. It’s used for anything from the detection of stress indicators in precision agriculture [ref] to studying skin disorders in human dermatology[ref] - and more recently for fruit quality control [ref].

Much like NIR methods, HSI uses non-ionising radiation outside of the visible light spectrum to measure a “spectral fingerprint” from a given sample. The key difference is that HSI uses not one, but typically hundreds of different wavelengths (colors) of light.

This rich spectral wealth captures lots of information about the fruit, but only from as far below the surface as the light can penetrate. Penetration depth depends on the wavelength used, and the tissue (fruit) type in question, but can be anywhere up to 4 mm [ref, ref, ref]. Accordingly HSI can simultaneously evaluate external and internal characteristics of fruit; for example to identify blemishes on the skin, as well as bruises and contaminants farther below.

Quantitative measurements are possible as with NIR, through correlation of shallow spectra to wet-lab analysis, requiring very large datasets calibrated to season and origin [ref, ref].. Typical parameters suited to HSI analysis include moisture content and dry matter [ref].

Ultimately however, HSI still relies on light penetration. Its vision is inherently limited by the optical properties and opacity of the fruit tissue itself, meaning deep internal assessment remains challenging. HSI is definitely something to keep an eye on over the years to come, as its broad scope of applications matures and evolves.

Microwave Sensing

Microwave sensing (MWS) is a slightly different technique, in which microwaves are projected into the sample to measure the dielectric properties of the tissue [ref]. These can be correlated to parameters such as moisture content and acidity, among others, making MWS a great bit of tech for quantitative measurements in fruit.

Interestingly, MWS came about as an accidental by-product of radar technology during the Second World War, and was first adapted for grain and lumber industries in the 1960s [ref, ref, ref].

MWS is not limited by penetration depth, using longer wavelengths to overcome tissue scattering almost entirely. The trade-off however is that these wavelengths in the tens of centimeters create a new blind spot: spatial resolution. While MWS can tell you the average moisture content across the fruit, it cannot pinpoint the small browning beginning deep down [ref].

Additionally, MWS tools are typically not integrated inline due to electromagnetic interference in factory environments, and the difficulty of achieving the mechanical coupling required between sample and sensor at high throughput (the sensor needs to physically touch the fruit!). Unfortunately, in practise this limits an otherwise powerful technology to hand-held devices only.

MWS may remove the guesswork around average quality of a given fruit, but it leaves producers vulnerable to the smaller localized defects that ultimately trigger consumer-end waste - and without scanning every fruit in-line, how can you really be sure of what is inside your fruit?

Tera-Herz Sensing

Recent advances are now closing the so called “Tera-herz gap” - a technological no-mans-land between electronics and photonics, giving coverage of the electromagnetic spectrum between 0.1 and 10 THz [ref]. What does this mean for sensing? X-ray-like technology using safe, non-ionising radiation.

THz sensing is revolutionizing precision-thickness measurements in industrial quality control of dry, non-conducting materials - but does it have the same potential for fresh produce?

Unfortunately, the physics that makes it so sensitive are also its downfall, and penetration depth is once again problematic. While it allows imaging through plastic and paper packaging materials, water absorbs THz signals so aggressively that penetration depth is often less than 1 mm for water-rich samples such as fresh fruit [ref, ref].

Despite being suited to spotting surface rot or inspecting dry foods (like nuts), it simply cannot see deep enough to check a seed inside a wet fruit.

THz sensing is a scientifically elegant solution for many areas of application, but for whole, fresh produce, it is too specialized. Relatively expensive and surface-limited, it fails to displace other cheaper, established tools already on the market, like NIR.

AI-Powered MRI

Last but not least, let’s take a look at Orbem’s solution - AI-powered Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) for fruit quality control (yes, you read that correctly) - total internal visibility in 3D, unhindered by surface or bulk opacity. In conjunction with state-of-the-art machine learning, Orbem turns complex MRI data into simple yes or no decisions for your packing line.

MRI might be a household name, yet few are familiar with its rich history, or even how it works - so let’s take a quick look under the bonnet.

The principles of nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) were theorized as long ago as the 1930s by Isidor Rabi, for which he received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1944 [ref]. Much later, the first MRI scan of a human was performed by Peter Mansfield and Paul Lauterbur in the 1970s, in turn commanding the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2003 [ref, ref].

Common misconceptions around MRI often include its use of ionising radiation or dangerous magnetic fields, but it is important to understand that this is fundamentally not true. MRI uses radiowaves, much like your wifi router and mobile phone. We are surrounded by radiowaves, with thousands of them passing safely through us every day, through our clothing and the walls of our houses.

While the systems do use low magnetic fields, they pose no threat to subjects or operators of the machines when operated correctly, and are objectively far safer than other clinical imaging systems such as X-ray or positron emission tomography (PET) [ref].

But most importantly: There is no limitation for penetration depth, as the magnetic field and radiowaves permeate the entire sample.

Read more about how Orbem uses Machine Learning to turn complex MRI data into actionable intelligence in this article.

A Brief Visual Summary

The Evolution of Fruit Quality Control

As demonstrated, the various technologies currently serving the fruit industry each involve specific trade-offs regarding penetration depth, spatial resolution, and ease of in-line integration. While established methods like NIR and HSI provide valuable surface and near-surface data, the industry's move toward a zero-waste supply chain is increasingly reliant on achieving high-resolution, volumetric data of the fruit's interior.

The introduction of AI-powered MRI into the industrial space represents the next step in this progression. By utilizing magnetic fields and radiowaves rather than light-based sensors, MRI can generate detailed 3D imagery that remains unaffected by skin thickness, color, or external density. This allows for the detection of deep-seated internal defects that have historically been difficult to identify without destructive sampling.

Ultimately, the transition from "guesswork" to data-driven quality control is what will define the next decade of fruit production. As these clinical-grade technologies become more accessible for high-volume industrial use, producers gain a more precise toolkit for reducing waste, managing logistics, and ensuring consistent quality across the global supply chain.

About the Author

Ben Danzer, Junior MRI Scientist

An imaging scientist with a background in medical physics, Ben explores the application and acceleration of AI-powered MRI in new markets here at Orbem. Before joining Orbem, Ben worked in pre-clinical nuclear medicine in Munich, as well as in various clinical microbiology roles in the Channel Islands.

.avif)